Nine young wild born captive orangutans whom Taiwanese officials had confiscated and one young orangutan whom Orangutan Foundation Taiwan (OFT) acquired for repatriation became known as the “Taiwan Ten” in the early 1990s. OFT and OFI worked to coordinate the return of the Taiwan Ten to Borneo. In mid-September 1990, Dr. Biruté obtained the import permits from the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) that were necessary to return the orangutans back to Indonesia. Marcus Phipps of OFTaiwan persuaded China Airlines to fly the Taiwan Ten to Indonesia at no cost. As word spread of this repatriation effort, Taiwanese government authorities launched an essay contest for school children and sponsored nine winners to accompany the Taiwan Ten on the flight to Jakarta. On November 28, 1990, those nine children, almost a hundred additional students who had paid their own way, their schoolteachers, and three OFTaiwan representatives accompanied the Taiwan Ten to Jakarta where the young orangutans were ceremoniously returned to a group of Indonesian children at the Jakarta Zoo. This repatriation was an unprecedented event and was covered extensively by national and international news media.

The Taiwan Ten were meant to go to Tanjung Puting National Park for rehabilitation after undergoing a four-to-six-week quarantine at a guest house at the Jakarta Zoo. But the Indonesian Director General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation (PHPA), the nature and wildlife protection agency at that time, subsequently refused to allow for their transport, began waffling on where to send the young orangutans, never assigned staff to care for the orangutans while they remained in limbo at the Jakarta Zoo, and after a month ceased to provide funding to care for the orangutans. During these stressful and uncertain times, OFI and OFTaiwan raised funds to ensure the Taiwan Ten received proper care in Jakarta. Three experienced OFI Indonesian staff from Camp Leakey in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) and undergraduate student volunteers from the Biology Department at Universitas Nasional in Jakarta took charge of caring for the Taiwan Ten for the next eleven months.

PHPA’s mismanagement of the Taiwan Ten’s repatriation and other conservation issues prompted a coalition of Indonesian conservationists and student groups to form. This group agitated loudly for the Taiwan Ten to be repatriated to Tanjung Puting National Park as was initially agreed upon. The media paid much attention to the situation. The situation got worse when the students and conservationists refused to turn over the orangutans to any party, including the PHPA agency, that would not send them to Tanjung Puting. Just after dawn on November 1, 1991, twenty Indonesian military men burst into the Jakarta Zoo guesthouse where the Taiwan Ten were being kept. Dr. Galdikas was warned of this coming intrusion the day before and was advised to leave Indonesia. She and her son Binti left that day for the closest “safe harbor,” Australia. The orangutans’ volunteer caregivers had also been warned the day before and a group of them escaped from the Jakarta Zoo guesthouse during the night proceeding the raid with all but one of the orangutans. Each of the nine male Indonesian students had escaped with the nine orangutans strapped to their bodies in the manner of a traditional Indonesian mother carrying her baby in a sarong. These were not infant orangutans; these were juveniles and adolescents. But they seemed to understand that something serious was going on and remained tranquil as night turned into day. By the time the military men arrived after dawn, instead of the ten orangutans they had expected, they were met with just one orangutan and over 100 Indonesian students and conservationists who had gathered there in protest. The one male orangutan left behind was too big and cantankerous to be carried by a student, especially strapped to the student’s body.

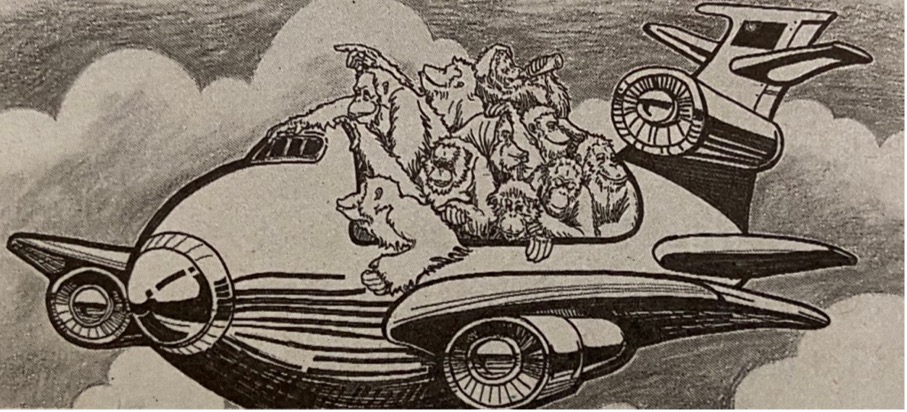

Receiving instructions from the OFI President and a concerned Board Member, the students engaged in nonviolent protest by kneeling and sitting silently, without confronting the astonished military invaders. However, the military detained fourteen of the students present at the guest house. The authorities expected that the orangutans, who were quite large, would be in transport cages, so they blocked all exits out of Jakarta and checked every truck that was leaving Jakarta at the time. On November 1, worried about their detained peers but not trusting the head of PHPA, the Indonesian students who had been riding throughout Jakarta in taxis during the night, changing taxis every half hour to avoid the authorities, with nine of the Taiwan Ten strapped to their bodies, went to the building where the Environment Ministry was housed. At dawn, the students and their nine large orange “babies” crept into the Environmental Ministry building, past the elderly sleeping security guard, and entered the waiting room in the Minister’s office. The Minister’s office was locked, but the door to the waiting room was open. After riding through the night, strapped to the bodies of nine students, the orangutans had a field day in the Minister’s waiting room, ripping curtains, throwing chairs, opening and tossing books from shelves, etc. When the Minister’s aides arrived in the morning and saw orangutans climbing and swinging from the office curtains, they immediately informed the Minister himself not to come.

The Universitas Nasional (UNAS) students formally turned over the orangutans to the respected Minister of the Environment, Emil Salim, whom the students said they trusted more than the head of the PHPA. Their fourteen UNAS student colleagues were released from custody but, unfortunately, a few of them had been beaten and ended up in the hospital.

Seven of the Taiwan Ten were sent to a rehabilitation in eastern Borneo and three were sent to a primate research facility in Bogor, just outside of Jakarta. OFTaiwan put its plans for further orangutan repatriations to Indonesia on hold until PHPA clarified its position on procedures for future repatriations. OFTaiwan continued on its path to change government and community attitudes towards the primate trade and exploitation in Taiwan.

But in the end, this ordeal represented a partial victory for the UNAS students and the conservationists who cared for the Taiwan Ten and campaigned on their behalf. According to inside information, President Soeharto, in his 35th year as President of Indonesia, accepted advice that the student protests were not anti-government but were focused on the conservation and environmental problems that were building in Indonesia. With one exception, there were no known repercussions against the students and conservationists involved in the Taiwan Ten protests on October 31st, 1991 – November 1st, 1991. Ironically, all the drama and attention surrounding the Taiwan Ten had brought much media and public attention across Indonesia to orangutan and forest conservation issues. In some ways, the UNAS student protest about the handling of the Taiwan Ten orangutans was a beginning turning point in public perception. For one thing, it was clear that the government of President Soeharto, in its own way, and even President Soeharto himself, had sympathy towards the conservation of Indonesia’s magnificent Nature and biodiversity. Some of those UNAS students involved in the protests over thirty years ago remained active in conservation for years to come.